(BBFC 15)

Calling himself a “Conscientious Co-operator”, Desmond Doss went to war. A Seventh Day Adventist, Doss refused to carry a weapon or work on a Saturday (the Sabbath in said church) and yet he managed to save the lives of seventy-five severely injured men from the blood-soaked killing field beyond the Maeda escarpment (the titular “Hacksaw Ridge”), Okinawa.

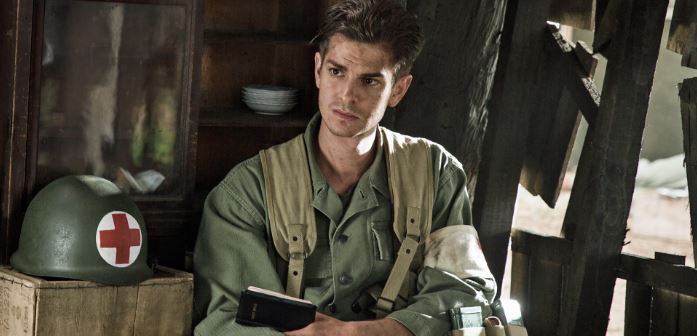

The movie begins in the Blue Ridge Mountains, Virginia where we follow the childhood and adolescence of Desmond (Darcy Bryce), the son of an alcoholic, damaged WWI veteran Thomas Doss (Hugo Weaving). It’s an “Aw, shucks” upbringing straight out of The Waltons, tinged with moments of sudden violence (such as hitting his brother in the head with a brick) and the constant threat of his father’s belt. It’s another belt, though, that provides the momentum to push the story forward when the slightly older Desmond (now played by Andrew Garfield) uses his as a tourniquet to save the life of a man trapped under a car. Not only does this incident provide Doss with a calling, it also brings him into contact with nurse Dorothy Shutte (Teresa Palmer) with whom he is instantly smitten and becomes the love of his life.

When most of his town, including his brother, enlist to serve to fight in World War II Desmond is compelled to join up to become a medic despite/because of his deeply held beliefs and the protestations of his father. Basic training at Fort Baxter becomes pivotal to the story as Doss refuses to pick up a weapon, a decision that brings him into conflict with not only the platoon’s hierarchy (Vince Vaughn and Sam Worthington) and his comrades but with the army itself. Life is made hellish for him as he is forced into endless menial and demeaning duties, beaten viciously by his ‘buddies’ and faces a court martial and it is only through the intervention of his father, ironically, that Doss is allowed to remain in the army and go to war.

Which brings us to the literal meat of the movie, the battle for Hacksaw Ridge. Remaining behind after a savage attack and even more bloody retreat, Desmond pulls man after wounded man from the charnel killing field and delivers them to safety. Despite the threat of multiple Japanese patrols, constant danger and exhaustion he continues to venture out to save, “Just one more”.

In many ways, Mel Gibson’s Hacksaw Ridge is a proper, old fashioned “war is hell” war movie on a scale not seen since Stephen Spielberg’s Saving Private Ryan or Sam Fuller’s The Big Red One, even. It’s a crowd-pleasing epic that tells of one man’s courage in the face of, not just, a relentless enemy but implacable bureaucracy and gung-ho bravado; it’s a tale of heroism that harks back to, and is akin to, classic Hollywood fare starring Gary Cooper or John Wayne or Jeff Chandler and wades through devastated landscapes of violence, action and gore to deliver a (mostly) true-story as inspirational as it is uplifting.

And yet, I found it deeply troubling. It works really well on a surface level but beneath that surface bubbles the director’s politick, a right-wing agenda that plays to Red-States America and the baser side of our nature. Gibson uses techniques perfected by the propagandist movie makers of the 1940’s, films used to drum up enlistments or demonise the enemy: The movie opens under bucolic Virginian skies, good ol’ boys drinking beer and church choirs assert the way of life under threat; before we even see the Japanese they are referred to as unkillable animals and, when we do see them, they are a horde not unlike the CGI waves of World War Z zombies, faceless, unstoppable and relentless; enemy bullets rip, tear and explode American bodies in huge meaty gouts of blood where allied bullets kill cleanly, humanely, because, remember, atrocities are only what the other guys carry out.

Mel just can’t help being Mel. There is much of his Passion of the Christ in Hacksaw Ridge, the camera lingering over the suffering and pain, the blood and injury, the slow-motion hero posing. There are direct lifts from other movies (most obviously during the basic training section of the movie in which the woeful Vince Vaughn attempts his best Full Metal Jacket) and moments that could only have come directly from the bizarro-mind of Mel (such as a weirdly glaring moment when a soldier uses a dead comrade’s torso as a shield as he charges, gun-blazing, into the enemy).

Hacksaw Ridge plays in entire counterpoint to Martin Scorsese’s Silence, a movie in which, once again, Andrew Garfield plays a man of faith venturing into the far east to find that his faith is tested. When Garfield’s Rodriguez asks of God all he receives is silence; when Garfield’s proto-Gump asks of God, God answers with explosions and the cries of the dying: “What is it you want of me? I don’t understand” BOOM! “This, you idiot”. Scorsese wants you to think about belief, to question, to find your own answers. Gibson wants you to know that his god is bigger than your god.

I didn’t like Hacksaw Ridge but that doesn’t make it a bad movie. It’s a great story and I have nothing but respect for Desmond Doss, there is nothing about Gibson’s film that you could ever call, “boring”, in fact it’s pretty exciting (albeit in a goofy kind of way). There’s much I don’t agree with in the movie but that doesn’t mean it’s not entertaining (which is why I gave it a 4-star rating). It’s a 1940’s war film made for a 2017 audience and that is its strength as well as being its weakness.