BBFC 15 2hrs 3mins

I was lucky enough to have seen Guillermo Del Toro’s The Shape of Water at last year’s London Film Festival (it was the hot ticket screening) and I have been thinking about it ever since. It’s a movie that can be enjoyed purely at surface level – a romantic fairy tale about a mute cleaning lady at a top-secret Government research facility who falls in love with a fish man – but it contains multitudes and the more thought I put into it the more pleasure I get from it.

Elisa (Sally Hawkins) lives a lonely, routine life in a shabby apartment above a movie theatre in Baltimore, 1962. Her best friends are Giles (Richard Jenkins), her closeted gay neighbour, and Zelda (Octavia Spencer), her chatty, brassy co-worker with whom she shares her secrets and scrapes gum from the floors of jet-engine laboratories. When a new “asset” arrives at the facility, along with its handler Richard Strickland (Michael Shannon), Elisa’s natural curiosity and compassion leads to an unlikely, inter-species relationship. The asset (Doug Jones), you see, is a humanoid, amphibian creature captured from deep within the Amazon by Strickland and brought to the lab’s in the hope that unlocking its secrets will give the US the edge in the Cold War in general and in the “Space Race” specifically. When it transpires that those secrets can only be revealed via the asset’s death and dissection it is up to Elisa and her friends to help it escape the facility and release it to freedom.

Whilst The Shape of Water can be enjoyed at its most basic fairy-tale level, a quirky riff on The Little Mermaid or The Creature From the Black Lagoon, a throwaway genre romance, it is when you start to unpack its many layers and storytelling choices that it reveals its true glory. Key amongst these choices is understanding the viewpoint from which the movie is told: The movie is bookended by Giles’ lyrical narration, how you react to the much of the film (and especially the ending) relies upon whether, or not, you believe him to be a reliable narrator. A subplot involving sympathetic scientist Dr. Hoffstetler (Michael Stuhlbarg) and Soviet spies which, on first viewing, appears to be ridden with clichés and rather silly makes a lot more sense when you understand that it is coming from Giles, whom it is established is a dyed-in-the-wool romantic fantasist. Just grasping this one simple device, I think, will give you a much more enjoyable and nuanced viewing experience.

Director Guillermo Del Toro (known, not only, for his audience pleasing genre crowd pleasers like Blade II, Pacific Rim and two Hellboy movies but his more arthouse fantasies Pan’s Labyrinth and The Devil’s Backbone) has absolutely stuffed the film with references, textures, metaphors and salutes. The Shape of Water is Del Toro’s love letter to Hollywood and, in particular, the movies that have influenced him. It is not difficult to see the spot nods to silent cinema (after all the two main protagonists, Elisa and the asset, are both mute, both silent); there’s a wonderful fantasy pastiche of Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers’ “Let’s Face the Music and Dance” sequence from Follow The Fleet; there’s quiet tributes to Powell & Pressburger, Vincente Minelli and Douglas Sirk and, most obviously, Del Toro’s love of classic monster movies. This is about as close to Del Toro’s Cinema Paradiso as we’re ever likely to get to or hope for, occasionally pausing to take in moments of real Hollywood gold (such as Shirley Temple dancing with Mr. Bojangles, Bill Robinson). Everything is imbued with meaning from individual props, the choice of colours, the choice of language, even Alexandre Desplat’s beautiful score harkens back to Hollywood romanticism. And all these things are not there to be clever or smart, they are there to move the story forward and provide texture and background.

In any other year you would nail on Sally Hawkins performance to win the Best Actress Oscar (such is the quality of her fellow nominees, especially Frances McDormand in Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri). There is never a single moment when you don’t know what she is thinking or feeling (emotionally), it’s a (largely) wordless performance and yet through her face and body language she says more than virtually any other actor on screen. Richard Jenkins is wonderfully sweet and affecting as the gay artist with one foot firmly in the dreams of Hollywood musicals and romantic yearnings for the guy who runs the pie shop. Octavia Spencer, always wonderful, provides the majority of the film’s humour as the sassy, vociferous and loyal Zelda. My only gripe with the film’s casting is that Michael Shannon is too perfectly cast as Strickland, we’ve seen him play similar roles too often for it ever raise a question in our minds as to who is the real monster of the piece? He’s great as a vile, entitled, toxic male who could sadly exist in 1962 or 2018, but as a subversion of the B-movie, lantern-jawed hero he’s just a wee bit too familiar.

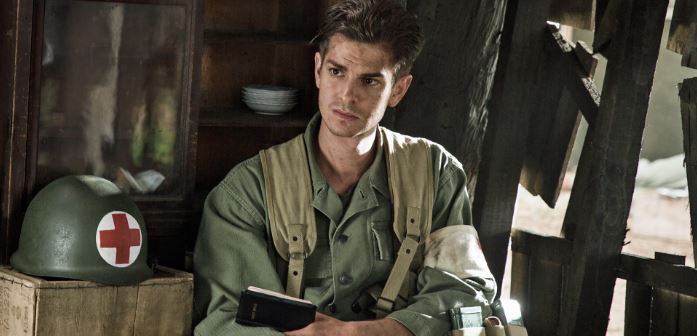

Not forgetting Doug Jones who, with a dancer’s physique, poise and grace brings The Asset to beautiful and vibrant life.

It may seem a little strange to give The Shape of Water a Valentines Day release, but it is, ultimately, a film about love and as Guillermo Del Toro so poignantly explained, “…love is like water, it has no shape. It can take the shape of whatever you pour it into. You can fall in love with someone that is twice your age, the same gender, completely opposite religion, the completely wrong political persuasion – it just happens. And it is, like water, the most powerful and malleable element in the universe. And it goes through everything.”